In contrast to some of the other symbols explored here, the ampersand seems at first sight to be entirely unexceptional. Another of those things the Romans did for us, the symbol started life as the Latin word et, for ‘and’, and its meaning has stayed true to its origins since then. Even the word ‘ampersand’ itself manages to quietly hint at the character’s meaning, unlike, say, the conspicuously opaque naming of the pilcrow or octothorpe. Dependable and ubiquitous, the ampersand is a steady character among a gallery of flamboyant rogues.

Things were not always thus, however. Today’s ampersand might take pride of place in the elevated names of Fortnum & Mason and Moët & Chandon, but its Roman ancestor was a different beast entirely. Born in distinctly ignoble circumstances and dogged by a rival character of weighty provenance, the ampersand would spend a thousand years of uneasy coexistence with its opponent before finally claiming victory. The ampersand’s is a true underdog story.

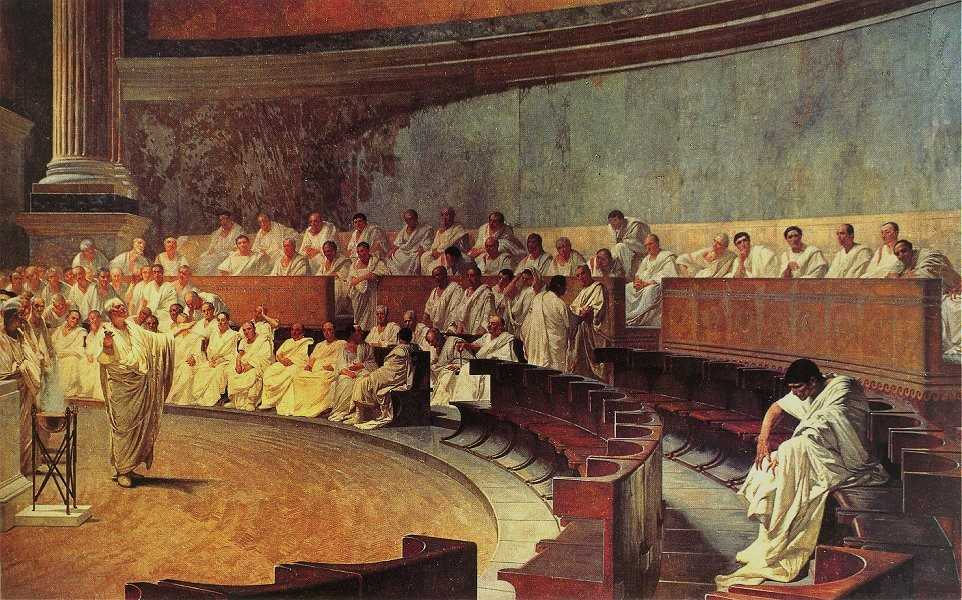

The first century BC politician, philosopher, lawyer and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero was one of that select circle of Roman personalities who, in the manner of the most prominent of today’s footballers and pop stars, could go by a single part of his tripartite name and yet still be instantly recognised. Cicero, as he is and was invariably known, was alternately immersed in and exiled from Roman politics at the highest levels. His life and works are a fascinating microcosm of a Republic groaning under its own weight.

Born in 106 BC to an aristocratic but hitherto undistinguished family, on the face of it Marcus Tullius Cicero was an unlikely candidate to succeed within the Republic’s rigidly hierarchical society. Political office in Rome was the preserve of a wealthy elite who had held the reins since its very founding,1 and as the scion of a family of neither notable wealth nor patrician stock, Cicero faced an uphill struggle for acceptance. Running afoul of another traditional Roman prejudice, Cicero was not in fact a native of Rome itself but instead a small provincial town to its south. Most unfortunate of all, though, his very name counted against him: his now-famous cognomen, or personal surname, meant ‘chickpea’; apparently inherited from a cleft-nosed ancestor, it was not the most stirring of names for an aspiring politician.2 The insecurity he felt at the disadvantages arrayed against him left the young Cicero with a fierce desire to succeed. Adopting the Homeric motto “Always to be best and far to excel the others”,3 he would live up to it in spectacular fashion.

A lawyer by his mid-twenties, Cicero used wisely the opportunities afforded by his vocation, becoming a practised orator, cultivating political contacts and coming to public notice at the head of high profile cases.4 Making the leap from law to public service, he scaled the political ladder known as the cursus honorum, or ‘honours race’, with almost indecent haste, elected at the first try and the youngest legal age to each of the successive political offices of Quaestor, Aedile and Praetor.5 His meteoric rise culminated in 63 BC with his election to the Republic’s highest office: that of Consul, one of two equal partners who served a one-year term and who held the power of veto over each other’s actions. With a deal in place guaranteeing his corrupt and inept co-Consul Gaius Antonius Hybrida a lucrative provincial governorship in exchange for his quiescence,6 Cicero was the de facto civilian leader of the Republic.

Early in his year in office, word reached Cicero of the prospect of a coup orchestrated by Lucius Sergius Catilina, one of his defeated opponents for the position of Consul, and the protégé of a cabal of reformists seeking to reduce the Senate’s power. By then a shrewd politician, Cicero had cultivated a network of informants in the slippery world of the ruling classes, and was thus warned of an impending attempt on his life. Posting guards at his house to thwart the assassins, he stood before the Senate the very next day to deliver a scathing speech designed to turn popular opinion against Catiline and his cronies.6 Its opening words are well known to scholars of Latin:

Quo usque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra? quam diu etiam furor iste tuus nos eludet? quem ad finem sese effrenata iactabit audacia? (How far, finally, will you abuse our patience, Catiline? For how long will your frenzy still elude us? To what limit will your unbridled brazenness flaunt itself?)7,*

The conspiracy was thrown into disarray: exposed, Catiline fled first the Senate and then Rome itself, hoping to muster his army and seize power by force, while his accomplices remained in the city only to be discovered and imprisoned. Cicero pressed his advantage, delivering another impassioned speech to convince the Senate to have the conspirators put to death without trial.10 The conspiracy was ended, but the controversy over Cicero’s actions rumbled on. By flouting the laws of the Republic he had given the reformists — not least among them a certain general named Gaius Julius Caesar — the means to put him on trial and subsequently banish him from Italy.11

Cicero’s turbulent life could have filled any number of books, and being a particularly ardent self-promoter, he made a game attempt to write at least a few of them himself. He published his speeches as pamphlets to promulgate his views; he wrote a variety of philosophical treatises during his time in exile, and his voluminous correspondence was hoarded by his closest friend Atticus and published posthumously by Cicero’s indispensable secretary Tiro.12 Most apposite to this story, though, is the manner in which Tiro recorded his master’s spoken words.

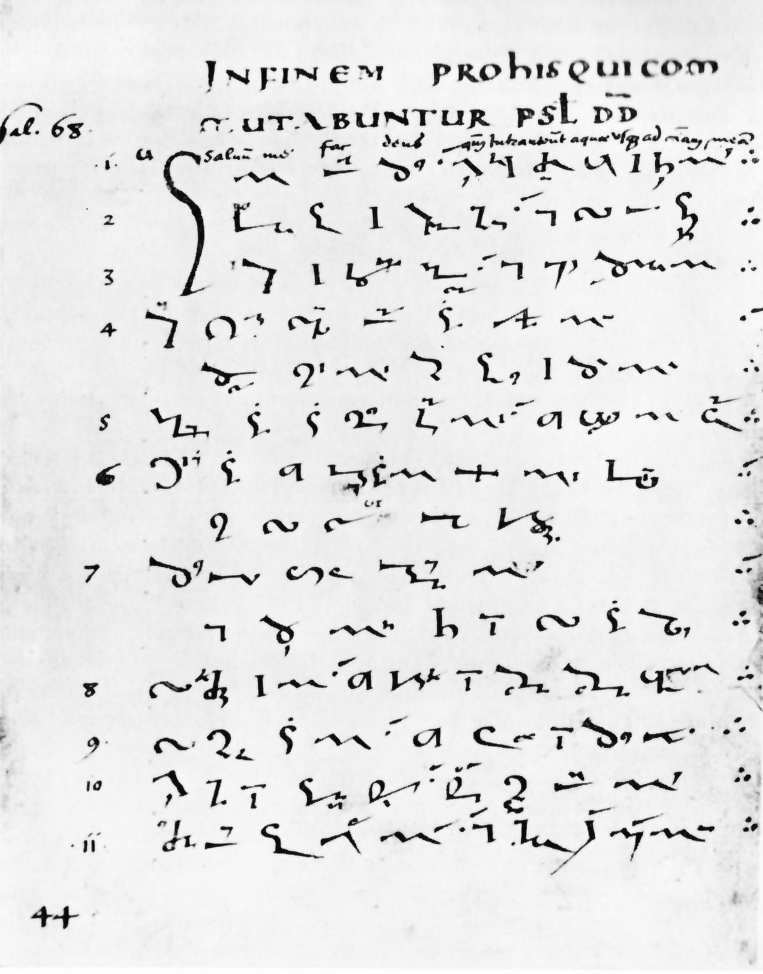

Born a slave of Cicero’s household (but later freed, styling himself Marcus Tullius Tiro), Tiro was a gifted scribe who became Cicero’s secretary, biographer and confidante, making himself “marvellously useful […] in every department of business and literature”.13 Following a tour of Greece some years earlier, Cicero had come away impressed by Greek shorthand and directed Tiro to create a similar system for Latin.14 In response, Tiro devised a system composed of Latin abbreviations supplemented with Greek shorthand symbols, modifying and expanding it by degrees to yield a cipher all of its own. The resultant notae Tironianae were an effective secretarial tool: as Cicero boasted to Atticus in one of his regular letters,15 Tiro could record not only words but entire phrases and sentences in shorthand,14 and it was in this way that the famous Catiline Orations were recorded for posterity. Posterity would, of course, have to be content with Cicero’s massaged versions of Tiro’s original notes.

Among Tiro’s notae was the so-called ‘Tironian et’, or ‘⁊’, an innocuous character representing the Latin word et.16 And though this was only one symbol among many (in their most elaborate medieval form, a system descended from Tiro’s original cipher comprised some 14,000 glyphs17), the utility of Tiro’s system ensured that it would remain common currency for over a millennium. The provenance of the Tironian et was mighty indeed.

When the ampersand first came to light a century after Cicero had delivered the Catiline Orations, it emphatically did not issue from the grandees of the Roman establishment; instead, it came quite literally straight from the streets. If the Tironian et was Tiro’s brainchild, the ampersand was an orphan: its creator is not known, and the closest it comes to a parent is the anonymous first century graffiti artist who scrawled it hastily across a Pompeiian wall.18

Exactly when this first recorded ampersand was written is not known, but the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD19 does impose a rather hard upper limit on the possible range of dates.

This first century ampersand is an example of a ‘ligature’, a single glyph formed by the combination of two or more constituent letters. Modern day ligatures, found in metal type or digital typefaces, appear where two or more adjacent letters are difficult to ‘kern’, or space correctly, and are often subtle enough to escape notice unless the reader is alert to their presence.20 The most common ‘functional’ ligatures in English are ‘fi’, ‘ff’, ‘fl’, ‘ffi’ and ‘ffl’,† while a type designer may choose to provide additional pairings like the purely decorative ‘st’, the archaic ‘ſb’,‡ or even the extravagant ‘fffl’, employed solely in the German word Sauerstoffflasche, or ‘oxygen tank’.22

The Pompeiian ampersand is instead a product of a simpler time when handwritten ligatures were time-saving contractions, the result of happy coincidence where the final stroke of one letter led neatly to the first of the next. Still clearly recognisable as the word Et, this ampersand only barely qualifies as a ligature at all, with the middle arm of the ‘E’ touching the stem of the ‘t’ in a suspiciously coincidental manner. Intentional or not, it is tempting to imagine that the ampersand is the result of an accidental slip of its doubtless nervous writer.

Whatever its origins, just as Cicero decisively overcame the prejudices he faced from the Roman establishment, the scrappy ampersand would go on to usurp the Tironian et in a quite definitive manner.

- 1.

-

Smith, William. “Patricii”. In Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 875-877. London: Walton and Maberly, 1853.

- 2.

-

Everitt, Anthony. “Always Be the Best, My Boy, the Bravest”. In Cicero : The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician, 21-46. Random House, 2001.

- 3.

-

Tempest, Kathryn. “The Making of the Man (106-82 BC)”. In Cicero : Politics and Persuasion in Ancient Rome, 22+. Continuum, 2011.

- 4.

-

Everitt, Anthony. “The Forum and the Fray”. In Cicero : The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician, 47-66. Random House, 2001.

- 5.

-

Tempest, Kathryn. Cicero : Politics and Persuasion in Ancient Rome. Continuum, 2011.

- 6.

-

Everitt, Anthony. “Against Catilina”. In Cicero : The Life and Times of Rome’s Greatest Politician, 87-112. Random House, 2001.

- 7.

-

Dominik, William J., and Jon Hall. “Cicero As Orator”. In A Companion to Roman Rhetoric. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- 8.

-

Johnson, A. F. Type Designs: Their History and Development. Grafton, 1959.

- 9.

-

“Letters”. The Linguist : Journal of the Institute of Linguists 38-41 (1999): 151+.

- 10.

-

Smith, William. “Catalina”. In Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology., 631-632. C.C. Little and J. Brown; [etc., etc.], 1849.

- 11.

-

Smith, William. “Cicero”. In Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology., 713-714. C.C. Little and J. Brown; [etc., etc.], 1849.

- 12.

-

Fishwick, Marshall William. “Two Pivotal Essays”. In Cicero, Classicism, and Popular Culture. Haworth Press, 2007.

- 13.

-

Cicero, Marcus T. “Book VII”. In Letters to Atticus, edited by E O Winstedt, 2:35+. Heinemann, 1913.

- 14.

-

Di Renzo, A. “His master’s Voice: Tiro and the Rise of the Roman Secretarial Class”. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication 30, no. 2 (2000): 155-168.

- 15.

-

Cicero, Marcus T. “Book XIII”. In Letters to Atticus, edited by E. O. Winstedt, Vol. 3. Heinemann, 1918.

- 16.

-

Russon, Allien R. “History and Development of Shorthand (shorthand)”. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- 17.

-

King, David A. “On the Greek Origin of the Basingstoke Ciphers”. In The Ciphers of the Monks: A Forgotten Number-Notation of the Middle Ages. Franz Steiner Verlag, 2000.

- 18.

- Unknown entry ↢

- 19.

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Vesuvius (volcano, Italy)”.

- 20.

-

Bringhurst, Robert. “3.3 Ligatures”. In The Elements of Typographic Style : Version 3.2, 50-53. Hartley and Marks, Publishers, 2008.

- 21.

-

Bringhurst, Robert. “Long S”. In The Elements of Typographic Style : Version 3.2, 312+. Hartley and Marks, Publishers, 2008.

- 22.

-

“Requiem: Features”. Hoefler and Frere-Jones, June 11, 2011.

- *

- Cicero’s words had, and still have, a habit of insinuating themselves into the world of typography. The Catiline Orations were used as the content of specimen sheets issued by the 18th century English typographer William Caslon, illustrating the appearance of his fonts,8 while the ‘Lorem ipsum’ boilerplate text used by printers and designers is a deliberately jumbled extract from Cicero’s On the Ends of Good and Evil.9 ↢

- †

- The web browser in which you view this page will determine whether or not such ligatures are used to render appropriate letter combinations, and at the time of writing, only Mozilla Firefox correctly uses available ligatures. Compare ‘shuffle’ with ‘shuffle’, or ‘fine’ with ‘fine’: rendered properly, the second word in each pair uses ligatures while the first uses separate glyphs for each letter. ↢

- ‡

- This ligature employs the archaic ‘long s’ letterform, ‘ſ’,21 whose unfortunate resemblance to ‘f’ caused it to fall out of common usage by the end of the eighteenth century. ↢

Comment posted by John Cowan on

Was and is invariably known? I think not. In England from the revival of learning to the 18th century, Cicero was “Tully” or “Master Tully”. Indeed, the identity of Cicero and Tully forms one of the stock examples of the concept of referential opacity: though you may know that Cicero was a great Roman orator, you may well not know that Tully was a great Roman orator, if you don’t know that Cicero is Tully. (The other stock example is Hesperus and Phosphorus, the planets that turned out to be just one planet, Venus.)

Note that the Tironian et is still in use in Modern Irish as the abbreviation for agus ‘and’. Indeed, standard Irish typewriter keyboards provided it. The Royal keyboard, which was intended for both English and Irish, had both ⁊ and &, just as it had both Irish and English forms of D, G, and T on different keys.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi John,

Thanks for the clarification — I wasn’t aware of Cicero’s earlier alias. I’m more or less learning all of this as I go along, so it’s great to have such knowledgeable readers here to pick up the slack.

Also, look out for the use of the Tironian et in modern Irish Gaelic in part 2 in a couple of weeks’ time. Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by The Modesto Kid on

Wiki page on Tironian notes shows a traffic sign in Ireland with the Tironian et on it. (Funnily enough the sign also has an ampersand on it.)

Comment posted by iDGS on

Thanks, this helped, as all direct references to atironian “et” in the article above just show up as (“glyph not found”) boxes on my iPhone 4. :-(

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

The presence of a Tironian et glyph on any given computer does seem to be a bit hit and miss. I’ve expanded the set of fonts available to render problematic characters like the Tironian et and the gnaborretni, but short of moving to web fonts I’m not sure there’s much else I can do at the moment. Even then, finding a font which supports those characters would be an odyssey in itself!

I’m sorry for the inconsistencies, and with a bit of luck I’ll be able to fix them at some point in the future.

Comment posted by Solo Owl on

Apparently that picture has been replaced by a monolingual “pay and display” sign. (Do they want foreign tourists at that location‽) A bilingual sign with ⁊ in the Irish part and & in the English appears on page 74 of the Shady Characters book.

Comment posted by HP on

Sauerstoffflasche, or ‘oxygen tank’.

And by an odd coincidence, “ſb” appears in the English word “gaſbag.”

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

HP — ouch! Very droll. Thanks for the comment, and I hope you enjoyed the post.

Comment posted by MM on

No mention of Robert Harris’s Cicero trilogy? (Tiro the narrator)

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi MM — good point! Perhaps I can include that in a future update.

Thanks for the comment.

Comment posted by Geof Huth on

Back in graduate school, while studying Old English, I ran across the Tironian et without knowing it had a particular name attached to it. I did, however, notice its clear resemblance to the numeral 7, and the fact that the 7 and the & share the same key on the now-standard Qwerty keyboard.

Geof

Comment posted by The Modesto Kid on

Whoa — interesting! I wonder if there’s any historical significance to that.

Comment posted by The Modesto Kid on

Apparently on old Irish typewriter keyboards, the Tironian ‘et’ was the shifted 7.

Comment posted by Solo Owl on

In this Hoefler font the Tyronian ⁊ and the numeral 7 can be distinguished only by subtle differences in line widths. Tyronian notes really should be given a more calligraphic twist, as in the font Code2000.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hmm — that’s an interesting point. Is it not the case that typefaces tend to move away from calligraphic scripts, rather than towards them? Maybe the Tironian et simply needs a more distinct typographic treatment (some experimentation with serifs, perhaps?) rather than a more faithful “handwritten” form.

Comment posted by Dannii on

According to our source of all knowledge, Wikipedia, the fffl ligature can’t actually be used in Sauerstoffflasche because it is a compound word.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Dannii,

I noticed that too! I’m going to pretend I didn’t see it, though, because frankly an ‘fffl’ ligature is just too fantastically extravagant to ignore.

Comment posted by Gordon P. Hemsley on

Just a technical note: I notice you use a zero-width space to force the non-ligature characters to show. However, as far as I can tell, that’s technically incorrect—a zero-width space is still a space, so you’ve actually broken up a single word into multiple words, even though it doesn’t display that way.

You might want to look into using the CSS3-Fonts property ‘font-variant-ligatures’, which you should be able to set to ‘no-common-ligatures’ to prevent ligaturization. (I haven’t tested it, but I’ve read that it should work in Firefox 4+.)

http://dev.w3.org/csswg/css3-fonts/#font-variant-ligatures-prop

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Gordon,

You’re right about my use of zero-width spaces to force separate letters. I had a quick play around with Mozilla’s font variant CSS properties but they seemed to be a little unpredictable to me. Perhaps I need to look into them again.

It’s frustrating; as a software engineer who knows just enough about typography to be dangerous, I’m constantly frustrated both by the slow adoption of CSS3’s font properties and the inconsistencies between browsers. When it comes to things like ligatures, I often have to compromise and use a slightly hacky solution when the ‘correct’ approach is flaky, browser-specific or just plain not available yet.

Anyway, thanks for the comment, and I’ll investigate ligatures again when I get the time to do so!

Comment posted by Leonardo Boiko on

Wouldn’t U+200C, zero-width non-joiner, be adequate?

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Leonardo — short of CSS3 font properties, the zero-width non-joiner does sound like the next best thing to try. Thanks! I’ll give it a go as soon as get a chance.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Leonardo — I’ve now replaced zero-width spaces with zero-width non-joiners. Thanks for the suggestion!

Comment posted by Rachel on

It is really hard to read an article in all-caps!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Rachel — are you seeing the article in all caps? Which browser are you using?

Comment posted by Ron on

I think you have a typo there, “an wealthy”, instead of “a wealthy.”

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Ron — thanks for the notice. That should be fixed now.

Comment posted by @conorjh on

I was taught the Tironian et, the 7-like abbreviation for “agus”, the Irish word for “and”, it was common to regard it as the Irish ampersand, I always assumed it was derived from the shape of agus, but obviously it comes from the Latin written by monks.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Conor,

The 7/⁊ relationship is an interesting one — see this comment thread above. There’ll be a little more about the Tironian et in part 2, which should be published in a couple of weeks’ time.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by James on

Don’t you mean end of the 19th century for the S ligature? I’ve frequently seen it in 19th century books.

Jmes

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi James — you could very well be right. I used a reference from Bringhurst’s Elements of Typographic Style which suggested that the ‘long s’ was in decline by the end of the 18th century, but it’s entirely possible that it spilled over into the early 19th century.

Thanks for the comment!

Comment posted by andrew wilson lambeth on

i do hope that part two takes time out to include an attempt to account for victorian children’s rote learning of an extended 27 letter alphabet : the little darlings ended their classroom litany with ‘and-pussy-and’ . of course, the curling strokes of the traditional ampersand rather lend themselves to conversion into a drawing of a cat, and i think a few victorian illustrated abecedaria did just that . but, looking at your reproduction of the pompei graffito again, i realised that even the first ampersand would, with very little work, make an excellent vorticist cat . then i looked up gaudier-brzeska’s famous cat drawing and saw he’d got there first : give it a horizontal flip it ( careful ! it looks like it bites ) and you have a wonderful and-pussy-and !

[ wikigallery have the drawing at http://www.wikigallery.org/wiki/painting_217971/Henri-Gaudier-Brzeska/Cat ]

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for the comment! I’ll be talking a little about rote learning and the use of “and per se and” in part 2. I haven’t come across “and-pussy-and” before, though — do you have any references I might look at?

(Incidentally, I’d like to suggest that anyone blindly typing “and-pussy-and” into Google do so in the privacy of their own home, and shouldn’t expect too much in the way of typographic content as a result…!)

Comment posted by andrew wilson lambeth on

yup — i got a bit of that google ‘pussy’ problem at work the day i posted, and i shivered a little . you’d have to know a fair bit about the history of hornbooks, i suspect, to understand how ‘and-pussy-and’ came about—they’re the curious school-primer tablets children were taught to write on, the alphabets and edifying texts overlaid with sheets of translucent bone : early etch-a-sketches . but the books section of google does point you towards ernest weekley’s etymological dictionary, and he attests ‘and-pussy-and’ from southey, and even includes ’emperzan’—which elizabeth seems to have been nearly enquiring about, below—from a certain pett ridge ( perhaps a worrisome google itself ! ) . for myself, i can’t actually remember where i first came across and-pussy-and—neither southey nor ridge, for sure . i did once look into illustrated abecedaria, and maybe it came from there

Comment posted by andrew wilson lambeth on

list of synonyms for ampersand form l e horning’s a dictionary of slang and colloquial english, routledge, london new york, 1905 :

and-pussy-and : ann passy ann : andpassy : anparse : apersie : per-se : ampassy : am-passy-ana : ampene-and : ampus-and : am pussy and : ampazad : amsiam : ampus-end : apperse-and : empersiand : amperzed : zumzy-zan

if i ever learn the bass and start a band, i know what i’m going to call it ( and i don’t mean ‘and-pussy-and-the-pussies’ ) !

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Andrew,

Now that is comprehensive. Thanks for posting it here! Still no ’empershand’ or ‘epershand’, but I think ‘zumzy-zan’ might make up for it.

Comment posted by Elizabeth on

Loved this post! Do you have any follow-up on the ampersand’s close kin, the empershand?

Thanks!

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Elizabeth,

I’m afraid I don’t have any material on the ’empershand’ — do you have any pointers for me to look into? The closest I’ve seen to that word is ‘epershand’, which is apparently the Scots term for ‘ampersand’, and even then, despite being a Scot living in Edinburgh, I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone use it.

Anyway, I’m glad you enjoyed the article, and I hope part 2 lives up to the first one!

Comment posted by Keith (not Houston) on

Also a Scot, also living in Edinburgh (also, coincidentally, called ‘Keith’), I have seen ‘epershand’ written about in articles and in dictionaries, I have seen it used as an internet nick, and I have seen it used in a company name. But I have never heard it used by a Scot or anyone else to describe an ampersand.

‘Epershand’ sounds how I imagine I might pronounce ‘ampersand’ after a good number of fine Scotch whiskies…

Comment posted by Bill Thayer on

The ampersand is opaquely named in French, mind you: c’est une esperluète.

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

Hi Bill,

Thanks for the comment. My French, sadly, is limited to ordering beer and asking for directions — do you have any idea of the etymology of esperluète?

Comment posted by Bart on

I have to say that this is one of the few blogs I read where the comments are as entertaining to read as the posts.

Comment posted by Jesse on

I couldn’t agree more! Wonderful site and wonderful contributions from the reader base … time to subscribe to this bad boy! :)

Comment posted by Steve Hall on

Hi Keith!

Just wanted to say how much I’m enjoying this series! A writer friend of mine pointed it out to me, and within seconds of beginning to read, I’d eagerly added it to my feed reader. (Not that I intend to read your articles there—mostly, it alerts me to updates, so I can come directly to the source.)

As a writer and sometime copyeditor, I have a vast love of language and all its parts (I’m afraid I draw the line at linguistic annotation, though), and your series is adding immensely to my knowledge and my enjoyment. Looking forward to & part 2!

Comment posted by The Modesto Kid on

Speaking of ligatures between f and i — it just occurred to me that there must also be ligatures fí, fì, fï, etc.

Comment posted by Anthony Appleyard on

I haver used the Tironian et plenty times when typing in Anglo-Saxon language, but always as the number 7.

Comment posted by Sumner Stone on

A very well done summary of Cicero’s early life. One addition just for amusement before I read part two. The followers of Catalina retreated to Fiesole, the hill town that is now in the middle of Florence. The Roman army that pursued him made an encampment around the hill and that was the beginning of Florence.

Comment posted by Alexander on

Why do you have “Catalina” and not “Catilina” appear twice in the text???

Comment posted by Keith Houston on

A mistake, pure and simple! Thanks for catching that — I’ve updated the text accordingly.